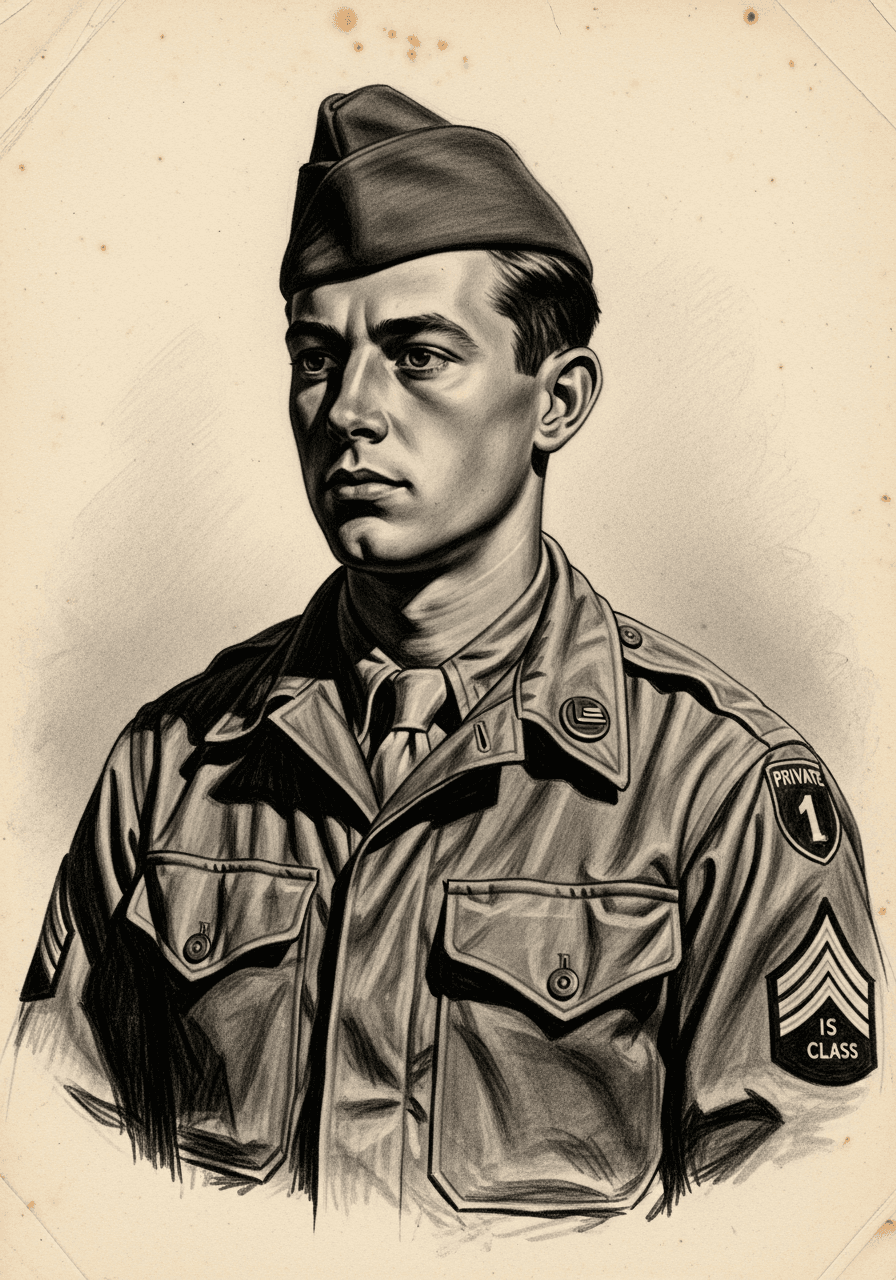

Sergeant Walter K. Williams, U.S. Army

Sergeant

Walter K. Williams

1913 — 1987

Pearl Harbor. The Rhine. Dachau. Bethlehem Steel.

A Life of Service

From the railroads of Pennsylvania to the beaches of Pearl Harbor, from the Rhine River to the gates of Dachau — the story of a soldier who gave everything.

1913

Born in Kittanning, Pennsylvania

Into a railroad family, Walter Kenneth Williams enters the world on November 9, 1913.

1920

A Meeting of Destiny

At age 6 or 7, young Walter holds infant Della Mae Murphy in his arms. Their families work the railroads together. He doesn't know it yet, but he's holding his future wife.

1933-1941

Civilian Conservation Corps

Under FDR's New Deal, Walter spends 7-8 years building America during the Great Depression. Roads, bridges, infrastructure. The skills he learns here will save lives in war.

December 7, 1941

Pearl Harbor

U.S. Army Engineer Corps in Hawaii. Walter witnesses the attack that draws America into World War II.

November 11, 1944

Ships to England

With the 257th Engineer Combat Battalion, Walter crosses the Atlantic. They land at Avonmouth, England, exhausted and uncertain of what lies ahead.

December 26, 1944

Crosses to France

The day after Christmas. The war begins in earnest. Cold, mud, and the reality of combat await.

March 26, 1945

Rhine Crossing

Under enemy fire, the 257th builds a 1,164-foot bridge across the Rhine. The 4th floating bridge to cross this formidable barrier. Three men die. Tanks roll across within 24 hours.

April 17-20, 1945

Battle of Nuremberg

The 257th fights not as engineers, but as infantry. Seven men killed. Heroes are made. Records aren't kept. The boys don't get the credit they deserve.

May 1-8, 1945

Dachau

They arrive at Dachau Concentration Camp. The odor of burning flesh still hangs in the air. What they witness will never leave them. "Death was King, and his throne a Crematorium."

May 8, 1945

V-E Day

"None of us could celebrate."

November 5, 1945

Marries Della Mae Murphy

The girl he held as a baby, 25 years later, becomes his wife. A love story that began in a railroad family, survived a world war, and lasted a lifetime.

1949-1952

Bethlehem Steel, Lackawanna, NY

Walter works at Bethlehem Steel. What he doesn't know: he is being secretly exposed to uranium. No protection. No warning. The government will hide this for 50 years.

1950-1953

Redrafted for Korea

At age 36, Walter is called back to serve again. Korea. Another war. Another sacrifice.

October 25, 1987

Dies of Lymphatic Cancer

Age 73. The uranium from Bethlehem Steel has done its work. Walter K. Williams is buried with his story untold.

2000

The Truth Emerges

The U.S. Government finally admits the secret uranium program. Thousands of workers were exposed. Many died of cancer.

2012

Settlement

The family receives $150,000 for his death. A fraction of what was owed. But an acknowledgment, at last, that Walter K. Williams was used by his country.

The Letter

June 24, 1945 — Germany. This 17-page letter was written by Major Vincent J. Bellis, commanding officer of the 257th Engineer Combat Battalion, to his wife.

It documents everything the battalion experienced from landing in England in November 1944 through V-E Day at Dachau in May 1945. Copies were distributed to the men of the battalion. Sergeant Walter K. Williams kept his copy, and it was passed down through his family.

Original letter preserved by the Williams family

The 257th Engineer Combat Battalion

The Rhine Crossing

On March 26, 1945, the 257th Engineer Combat Battalion accomplished what many thought impossible. Under constant enemy artillery and small arms fire, they built a 1,164-foot floating bridge across the Rhine River.

"The 4th Floating Bridge to be built across the Rhine, and the third ever to be built in wartime. So reads the commendation we received upon completion of this job."

The Cost

Three men gave their lives building that bridge. Six more were wounded. The work was completed in less than 24 hours. When the tanks of the 6th Armored Division rolled across, it marked a turning point in the war.

Later, at Nuremberg, the 257th fought not as engineers, but as infantry. Seven more men died. Bronze Stars, Silver Stars, Purple Hearts were earned — but without proper records, many never received the recognition they deserved.

"I never did feel so proud of anything in all my life, as I did when I saw those tanks of the 6th Armored go rolling across that Bridge."

Their Route Through Europe

From England to France, through the Siegfried Line into Germany. Towns passed through: Bristol, Southampton, Cherbourg, St. Lo, Nancy, Homburg, Mannheim, Wurzburg, Schweinfurt, Nuremberg, Munich, and finally — Dachau.

1,164

Feet of Bridge

24

Hours to Complete

3

Lives Given

Dachau

May 3, 1945. The 257th Engineer Combat Battalion arrives at Dachau Concentration Camp. What they witness will stay with them forever.

— From the letter of Major Vincent J. Bellis, June 24, 1945

Why This Matters

The documentation by ordinary American soldiers of what they witnessed at the concentration camps serves as an irrefutable record of Nazi atrocities. These weren't trained historians or journalists — they were engineers, mechanics, clerks, farmers. Their accounts carry a weight of authenticity that formal documentation cannot replicate.

Major Bellis wrote this letter just weeks after liberation. The details are raw, unprocessed. The horror is real. And for Sergeant Walter K. Williams and every man who stood in that camp, the memory never faded.

"The odor of burning flesh still hung heavy in the air when we arrived."

The Secret

After surviving Pearl Harbor, the European Theater, and Korea, Walter K. Williams returned home to work at Bethlehem Steel in Lackawanna, New York. He had no idea that his own government would betray him.

The Uranium Program (1949-1952)

During the Cold War, the U.S. government contracted with Bethlehem Steel to process uranium for the nuclear weapons program. Workers like Walter were exposed to radioactive materials without their knowledge or consent.

No protective equipment was provided. No warnings were given. The government classified the program and kept it secret for decades.

The Cover-Up

For 50 years, the federal government denied the program existed. Workers died of cancer. Families were told nothing. It wasn't until the year 2000 that the truth finally emerged.

The Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act (EEOICPA) recognized 22 specific cancers linked to radiation exposure at covered facilities.

Walter's Legacy

Walter K. Williams died of lymphatic cancer on October 25, 1987, at the age of 73. He never knew why he got sick. He never knew that his government — the same government he had served so faithfully — had poisoned him.

In 2012, 25 years after his death, Walter's family received a settlement of $150,000. The federal government had paid out over $25 billion in total settlements to affected workers and their families.

$25B+

Total Settlements

50

Years Hidden

"This man was used by his country and deserves to have his full story told."

The Family

Della Mae Murphy Williams

August 14, 1920 — March 30, 2005

Their love story began before she could even remember it. As an infant, she was held in the arms of a 6-year-old boy named Walter. Their families both worked the railroads of Pennsylvania. They grew up in the same world, the same community, the same faith.

Twenty-five years later, on November 5, 1945, Walter married the girl he had once held in his arms. He had just returned from Europe, from the Rhine crossing, from Dachau. She was there to help him come home.

Their Children

Mike Williams

Born 1947

Bill Williams

Born 1951

Gail Williams

Born 1955

Railroad Families of Pennsylvania

Both the Williams and Murphy families were railroad families, part of the backbone of American industry in the early 20th century. They built the infrastructure that connected a nation. Their children would go on to serve that nation in ways they never imagined.

A love story that began in a railroad family, survived a world war, and lasted a lifetime.